[S]

[S]

by Ed Nieuwenhuys & Cliff Lamere Feb 2, 2006

[S]

[S]

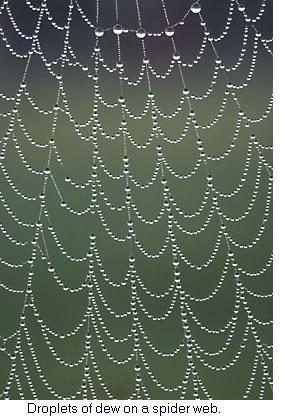

Orb web, heavy with dew

European Garden Spider (female) / Black and Yellow Argiope (female)

(Araneus diadematus) (Argiope aurantia)

Both spiders live in the U.S. They hang head

downward while waiting for a meal.

[This is a revision and expansion of a webpage originally written Aug 6, 1997 by Ed Nieuwenhuys of the Netherlands.]

Almost all spiders use a web to capture their food, but some do not. There are many different kinds of webs, some very unusual. The orb web spider makes the type of web pictured above and discussed on this webpage. When you think of a spider web, it is an orb web that you will likely be picturing in your mind. It is the best known. Spiders of other families construct other types of webs.

The diagrams below show how the European Garden Spider (Araneus diadematus) makes its web. This species is also found in eight states in the United States, including New York and Washington. Spiders of this species don't all make identical webs, so some of the steps may vary from spider to spider. The diagrams show what can generally be expected, even by other orb web spiders in the U.S. such as the Argiope spider seen above.

How does an orb web spider make its web?

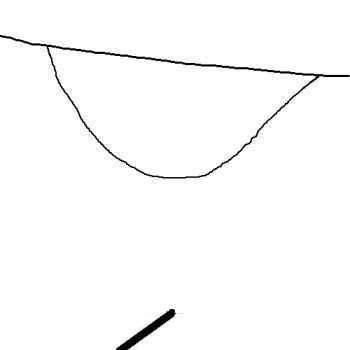

The most difficult part seems to be the first thread. Does the spider fly? Does she throw a line to the other side? Does she walk down and up at the other side carrying a thread that she attaches between the two sides?

No, none of these ideas are true. The solution is simple. In a slight breeze, the spider releases a sticky thread from her spinners, making it longer and longer. The very lightweight thread floats in the moving air (A single thread is so thin that it is invisible to the human eye). If the breeze carries the silken line more or less horizontally to a useful spot where it sticks, the first bridge is formed. If not, then the spider tries again.

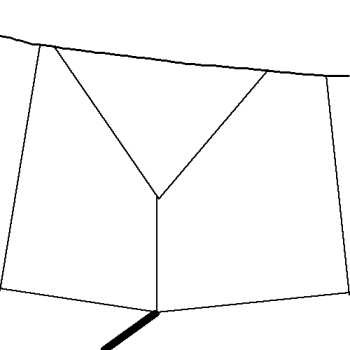

drawing by Samuel Zschokke

Next, the spider walks carefully along the thread, strengthening it with additional threads until it is strong enough to hold the weight of the entire web plus the spider and any food that gets caught. Then, the spider may construct a loose non-sticky thread above some object.

.

drawing by Ed Nieuwenhuys

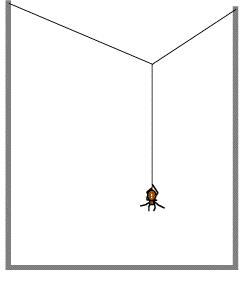

The center of the loose thread will become the center of the the spider's web.

The spider drops down from the center of the loose strand while spinning a new non-sticky thread.

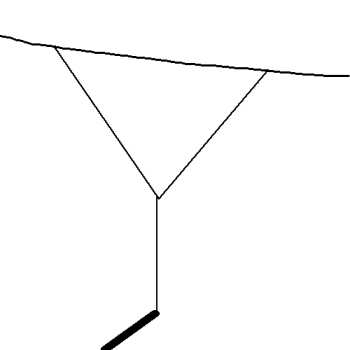

drawing by Samuel Zschokke

She pulls the new thread tight, and attaches it

to the object. The two threads form a Y shape.

These are the first three radii of the web.

.

.

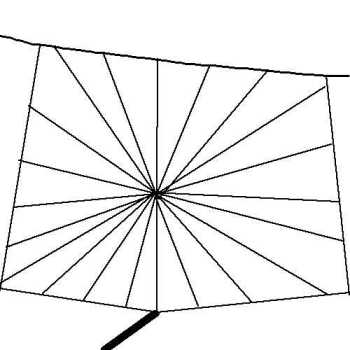

drawing by Ed Nieuwenhuys

Then a non-sticky frame is constructed to which the other radii can be attached.

drawing by Ed Nieuwenhuys

After that, additional non-sticky radii are made.

Everything in the next diagram is non-sticky

except the top reinforced thread.

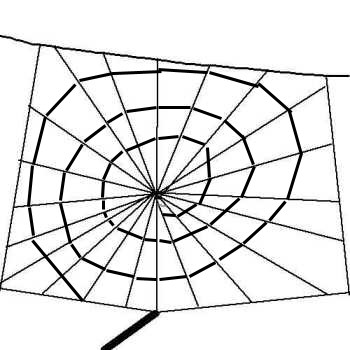

drawing by Ed Nieuwenhuys

Next, a non-sticky construction thread is made. The spider starts near the center

and makes a spiral thread that ends at the frame. The distance between the

parts of the spiral thread is made wide, but it must be narrow

enough so that the spider can span the width with her legs.

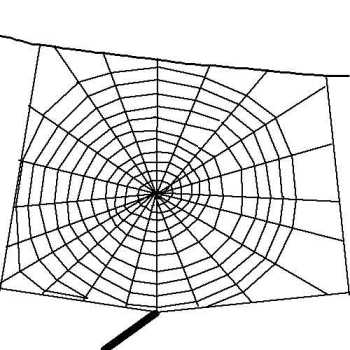

drawing by Ed Nieuwenhuys

Starting from the outside (after a rest), the spider begins to weave

the sticky spiral thread which will be used to capture food.

This thread is much closer together than the construction thread was.

As the spider lays new thread, it also eats the part of the

construction thread no longer needed.

.

drawing by Ed Nieuwenhuys

The spider hangs head downward in the center of the web (almost all spiders do). If an insect gets trapped, the spider can feel the vibrations from its struggle to get loose from the sticky silk. The spider springs into action and wraps its victim in another type of threads.

The silky threads of an orb web are too thin to be seen by the human eye. We can only see the web when light reflects off it or when dew or frost covers the threads. The captured prey must also have a difficult time seeing the web.

On the left is a photo of early morning dew on an orb web. The weight of the dew causes the thread between each pair of radials to droop.

Can you think of a reason why the dew drops are so much larger at the top of the photo?

[S]

[S]

[S]

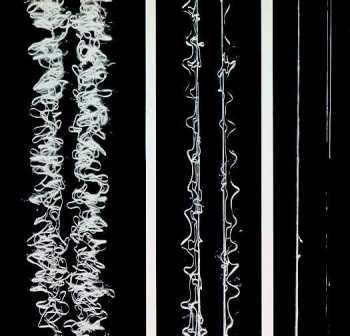

A large flying insect like a bee may strike the web with quite a bit of force. Why doesn't the bee break through the web? The answer is that the threads stretch. In the leftmost photo (at the right), you can see an unstressed thread. The middle photo shows the thread stretched to 5 times normal length, and the rightmost photo shows the thread stretched to 20 times normal length. When a bee hits the web, the threads simply stretch to slow the bee down, and then they return to their shorter length. The bee gets caught on the sticky threads.

Another reason that the web threads need to be stretchable is that a breeze can move the plants to which the web is attached. As the weeds move, the web must stretch or break.

In the photo above, the weight of the dew has caused each section of thread to stretch. Normally, the sections between two radials are shorter and nearly straight across, as in the two photos at the bottom of this webpage.

The European Garden Spider, an orb web spider, builds its web in the evening and hunts for food at night. Some damage does occur to the web overnight due to insect collisions. If the damage is minor, the spider may just repair the web and use it again the next night. Otherwise, the spider will eat its web in the morning, including any tiny insects sticking to it, except for the bridge thread that is the most difficult part of the web to create. Due to the fact that it has been reinforced, it is the thread least likely to have suffered damage from insect collisions overnight. Eating the web gives the spider the chemicals needed to spin new silk the following evening. The European Garden Spider rests during the day.

One of the best known orb web spiders in the United States, the Black and Yellow Argiope (Argiope auranteus), hunts during the day and rests at night.

The web in the right photo is hanging from Queen Anne's Lace plants.

Although the flowering structure is very flat on top, when it goes to seed, it curls into a ball.

Web and Silk (by Ed Nieuwenhuys) Look around on this great site about spiders.

"Movie" of the making of an orb web (Samuel Zschokke). On this site, move the round button (at the bottom) to the right with your mouse cursor, or click on the right arrow. You can do multiple clicks to watch one step at a time, or hold the mouse button down and the whole process will proceed rapidly.

Visitors since 30

Dec 2006

Go to the HOME page (Grandpa Cliff's Science Website for Teenagers)

Albany, NY